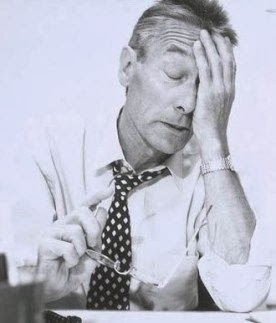

“Writing is easy: All you do is sit staring at a blank sheet

of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead.” -Gene Fowler

You have an idea.

Maybe it's a good idea. Maybe it's even a great idea. Your characters have started talking. You're ready to start writing.

Hold that pen, Slick.

How many times have you been down this path before? How many books have you started? Perhaps more importantly, how many have you finished? If the answer to that question is less than one, allow me to make a humble suggestion.

Plot first.

I've been down this road myself. I had already been writing for years before I finished my first book. That I never finished any of these earlier projects wasn't a huge deal to me. It was still just a hobby, after all.

When my son was born and I decided to get serious with my writing, I realized I needed to do things differently. In short, I needed to learn how to plot.

I proceeded to read a shit-ton of books on plotting and story-boarding/mapping/voodoo/whatever. The lightbulb came on for me when I realized I wasn't going to find all the answers all in one place. I still believe that early research was important, but more for recon purposes.

Since then, I've cobbled together my own approach from several of the books I read, including The Romance Writer's Handbook (Rebecca Vinyard) and Writing A Romance Novel For Dummies (Leslie Wainger). I found both useful in different ways, and cherry-picked different things from each.

Are you at a loss where to start? Looking for a simple, flexible way to plot your book? If so, stick close.

My (Unpatented, Super-Anal, Probably Thoroughly Unprofessional) Plotting Process:

*Note: I write romance novels. This is reflected in how I plot. If you write in other genres, you may still find this helpful, but you'll probably need to tinker a little more*

1) Create the characters. I have some basic character sketch templates I fill out before I start plotting. It helps me get to know who I'm dealing with.

2) Plot the relationship trajectory. I've read this referred to as the "Major Plot Points". They include any interaction between the hero and heroine that furthers their relationship (first meeting, first kiss, first sex scene, etc.).

3) Flesh out the rest of the plot. Think of it as "connect the dots", the "dots" being your Major Plot Points. What needs to happen to get from one dot to the next? This usually is where you insert your sub-plot, or the part of your book that doesn't have to do with the love story.

Then after all that's done...

- Go back and insert where the scenes/chapters start or end.

- Go back and insert where the scenes/chapters start or end.

- Go through, chapter by chapter, and outline everything (EVERYTHING) that is going to happen in that chapter, right down to when someone sneezes. Make note of any excerpts that pop into your head, any great pieces of dialogue, any description that needs to be woven in, that sort of thing. Keep all of this where you can refer to it easily (I have a notebook), and devote maybe one or two pages to each chapter.

- At the top of each page, define what your objective is for that chapter- increase sexual tension, flesh out characters, major turning points, etc. It helps you focus when you're actually writing. It's so easy to get carried away in the creative flow, it helps to have a visual reminder of what you're actually trying to accomplish.

- Finally, give yourself permission to completely change everything if you need to. I've noticed, especially after the first sex scene, the hero and heroine often go in a totally different direction than I had anticipated. It's a very organic thing, so make sure to leave room for the story and the characters to breathe.

Does it work? I've published three-going-on-four books since I started a little over a year ago, so I'll let you be the judge.

Starting out is always tough, but sometimes it helps to know it was (and is!) tough for other people too. I had a tough time starting. I think it was because I hadn't figured out who I was as a writer, and didn't realize I'm the type who needs to plot my stories out first.

If you're still reading, I assume you're ready to get serious. I hope this post provides some clarity. Kudos to you for knuckling down, asking questions, and figuring stuff out! A lot of people don't take that step.

Those are the people who end up writing journals, but not books.

.JPG)